Focus on Military Families, Part One: How to Support Military-Connected Students with Disabilities

Tuesday, November 04, 2025

For the 1.6 million U.S. children growing up in military-connected families, frequent moves and family separation are a challenging part of life. They will move and change schools, on average, nine times before high school graduation. For the roughly 20% of families whose children have disabilities, these changes can have outsize impacts (Aleman-Tovar et al., 2022).

Robyn DiPietro, EdM, is the Military-Connected Children and Youth Program Coordinator for OneOp at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign—a professional development resource for practitioners who serve military families.

“As a mom of multiple children with disabilities, it was always most comforting to me when one of my children’s providers or teachers really knew or had personal experience with the military,” DiPietro says. “Professionals can’t just run out and join the military to gain that experience, but they can educate themselves and become aware of what military life is really like and the impacts it has on the family.”

Here’s the advice she offers clinicians and educators who work with military-connected families.

Effective support for military-connected students starts with understanding the stress of deployment and relocation. Educators, school psychologists, school-based practitioners, and special education professionals can foster belonging by coordinating transitions, offering flexible supports, and strengthening family-school partnerships.

Understand the Needs of Military-Connected Students

A solid body of research confirms that military-connected students share a challenging set of experiences, including:

- Deployment and family separation

- Frequent moves and resettlements

- Trauma, uncertainty, and anxiety

- Educational disruption

As a result, military-connected students are less likely to be engaged at school (Soto et al., 2025). Lots of factors contribute to that lack of engagement. A family may have limited school choice by the time a transfer takes place. Curricula and academic standards vary widely across the country, so students are likely to discover they are ahead of or behind students at their new schools—or that coursework they completed at one school has no equivalent at another. Tryouts for sports teams or performing arts productions may already have taken place, keeping students from participating in activities that might promote new friendships and resilience.

That’s not to say that students in military families all have the same degree of difficulty adjusting to new settings. Strong family bonds, cultural assets, and caring educators can be protective factors. Without these supports, students are at a higher risk for developing problems with self-regulation, aggression, attention difficulties, and social withdrawal. Anxiety and depression may follow (Martin et al., 2025).

For the families, parents, and caregivers of students with disabilities, deployment and relocation may mean additional difficulties such as these:

- Receiving a diagnosis in one setting, then moving to another setting

- Requesting accommodations when documentation is in transit

- Resolving conflicts between school or provider timelines and military timelines

- Searching for organizations, providers, and services in each new area

- Navigating unfamiliar service delivery systems

- Advocating for a child while coping with their own anxiety and disruption

“Military-connected families move, on average, every 2-3 years, making continuity of care challenging,” DiPietro explains. “For example, a family may currently reside in North Carolina and experience a Permanent Change of Station (PCS) to Colorado. These two states have their own early intervention (EI) and special education systems and may have guidelines or policies related to EI and special education services that differ from one another…This can lead to confusion for families, as what their child received in one state may not be provided in the new state.”

Some of these challenges can be avoided. The Interstate Compact on Educational Opportunity for Military Children is a promise made by all 50 states and the District of Columbia to “eliminate some of the roadblocks military kids face transitioning to new schools.” Maintained by the Military Interstate Children’s Compact Commission (MIC3), the Interstate Compact is a set of rules to make enrollment, placement, attendance, eligibility, and graduation more efficient for military children. Each state has a compact commissioner and council. Schools can work with these officials to make transitions easier.

Build on the Strengths of Military-Connected Families

More research focuses on the challenges of growing up in a military-connected family than on its benefits (Opie et al., 2024). The Military Child Education Coalition (MCEC) reports that children in military-connected families:

- Have a broad range of cultural experiences

- Form connections with other people quickly

- Navigate and adapt in new circumstances

- Develop “social awareness skills” and an “expanded worldview” because they interact with people of many backgrounds

MCEC points out that, in general, children in military-connected families benefit from “steady income, residential stability, comprehensive health care, and educational assistance” (MCEC, 2022).

“Military-connected families can be resourceful,” DiPietro says, “but it can take time to develop that resourcefulness. The younger the family or the newer they are to the military, the less they may know about navigating the systems around them. However, over time many become very adept at ensuring their children’s educational needs are met and their child receives the services for which they qualify.”

Many military families develop strong connections to others in their community and may already have friendships in the area where they are relocating; social media can facilitate those connections.

“I hesitate to highlight this next strength, only because it can sometimes be misunderstood. But military families are strong and resilient,” DiPietro points out. “That does not mean they don’t need or want support. It does not mean we don’t have to concern ourselves with them or that they can handle anything with grit and grace. They are human just like everyone else. They feel stressed and burdened and sometimes lost and overwhelmed. They have varying support needs, but their capacity to move through challenges should not be underestimated.”

Develop a Supportive School Culture

Many aspects of a military family’s life will be outside your control—but as school-based practitioners and educators, you can create a school environment where military children with disabilities are accepted and supported. Here are a few ways to foster a sense of belonging in your school.

Listen to children.

When Australian researchers interviewed children in military-connected families, they found them to be “adept communicators” and “experts in their own lives.” They encouraged educators to provide more opportunities for children to tell their stories using different means and media, because children’s knowledge can help adults make better decisions about their care (Rogers et al., 2024).

Develop flexible processes.

People in military-connected families may have untraditional roles, and they may be navigating several systems at once. Scheduling and logistical difficulties may be easier to resolve if your team can be flexible about meeting times and places. “Military service members may work odd days and hours and need appointments at non-traditional times or via virtual platforms to participate,” DiPietro says. “It may also be necessary to meet in the community if the provider cannot access the installation.”

Maintain up-to-date records.

Incomplete or missing documentation can disrupt a smooth transition, DiPietro says, “making it hard for the receiving agency to have a good idea of what the child’s Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) or Individualized Education Program (IEP) from the sending agency contained.” Detailed, clearly written plans “make it easier for receiving teams to implement what was already in place for the child,” she says.

Prioritize information-sharing.

“Both military-connected families and the professionals that serve them may be unaware of or unfamiliar with the military- and civilian-related resources and services available to the family,” DiPietro says.

That is true, in part, because different branches of the military, military installations, state, and local programs offer different resources, in addition to the core benefits all families can access.

“Families may not know how to refer their child to early intervention in a new location,” she points out. “Many states have different names for their EI services. For example, Texas’ EI system is known as Texas Early Childhood Intervention Services (ECI), whereas Californian’s EI system is called Early Start. These names are similar but not the same and can result in confusion for families.”

Assess the need for emotional support.

Families, school psychologists, and school counselors may find it helpful to collaborate with Military Family Life Counselors (MFLC), who are adept at helping families cope with deployment, relocation, and reintegration. It’s also important to screen for anxiety and depression. Researchers who explored long-term mental health and social outcomes in both military-connected children and civilian children recommended “targeted screening and ongoing monitoring across childhood” to lower risks and improve social and emotional well-being (Opie et al., 2024).

“The emotional stress of a deployment can be felt by all members of the family,” says DiPietro. “Consider ways to support the family in whatever circumstance they are in, and ask them what their current needs are. Learn more about the deployment and PCS experience so that you can offer practical ideas and supports if they are too overwhelmed to generate their own ideas.”

Pursue specialized training.

A growing number of organizations offer professional development and training for providers and educators who work with military families who have children with disabilities. You may want to explore training opportunities through these organizations:

- OneOp

- Military Child Education Coalition

- Exceptional Family Member Program

- Clearinghouse for Military Family Readiness at Penn State

Discover how powerful it is when the whole school is trauma-trained.

Key Messages

Every educator has an opportunity to foster a sense of stability, security, and belonging in military-connected students and families. We can start by learning about military culture, including the unique strengths and challenges military-connected families face.

“I cannot tell you the number of times people say, ‘I don’t work with military families,’ and as soon as I explain the residential location of most military families, a light goes on, and they suddenly see how much they need to know to best serve the military-connect children and families with whom they work.”

With trained, responsive professionals on both “sending” and “receiving” teams, we can adapt processes so they’re more flexible. And we can collaborate with each family so there’s as much continuity as possible when it’s time for the family to change locations.

Blog

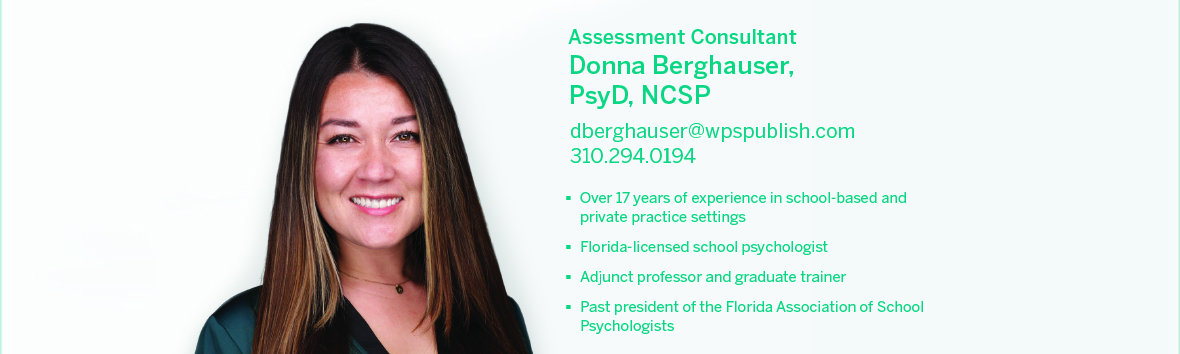

Focus on Military Families, Part Two: A School Psychologist Reflects on Her Military Upbringing

As a licensed school psychologist, Donna Berghauser, PsyD, NCSP, has nearly two decades of experience in schools and community practice settings. She draws on personal experience to offer guidance to other professionals working with military-connected families.

Read More >

Glossary

Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA): A federal agency that operates pre-K–12th grade schools and educational programs for the children of service members.

Educational and Developmental Intervention Services (EDIS): A program that conducts developmental screenings and provides early intervention services for children from birth to age 3 when families live on a military base with a DoDEA school. EDIS implements IDEA requirements for children who are eligible.

Exceptional Family Member Program (EFMP): A military program that supports families with special health or educational needs. It’s mandatory for active-duty service members with a family member who has a qualifying disability.

Military Child Education Coalition (MCEC): A professional organization that provides training and resources to support families and educators in improving educational and social outcomes for children in military-connected families.

Military-connected family: A family in which at least one parent is on active duty, in the National Guard, or part of the Reserves.

OneOP: An organization that provides evidence-based professional development and resources to support professionals who work with military-connected families Permanent Change of Station (PCS): Official military orders to relocate. A PCS is a longer-term assignment, often 2–4 years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Who provides early intervention services for military-connected children with developmental delays?

A: If a family is stationed within the continental U.S. and lives on an installation with a DoDEA school, early intervention services are provided by EDIS. If a family is assigned to an installation but lives in the community, services are provided through civilian early intervention programs. EDIS serves children birth to 3 years of age. Children ages 4 years and older receive services through their schools. If a child needs services that EDIS does not provide, families may be able to coordinate with a community-based service provider, often through the EFMP.

Q: How might the stress of family separation or deployment affect assessment results?

A: Emotional distress can look like learning or attention difficulties. Inattention, distraction, and emotional withdrawal can affect how a student performs during an evaluation. Using social-emotional screeners or anxiety and depression assessments in conjunction with learning measures can give you a more complete picture—both now and as a student adjusts over time.

Q: What should schools do when a family receives orders to move when a student is mid-evaluation?

A: The new school and current school should coordinate right away. Federal law requires the new school to provide the student with comparable services until the new district completes an evaluation or accepts the existing IEP. Document the results of the assessments you’ve already completed and share it securely to prevent delays.

Q: Which assessment tools or practices are most helpful for military-connected students who move often?

A: Evaluations should include a variety of assessment methods yielding data from those who know the student best. It may be more effective to rely on assessments normed on national populations rather than those that are based on state standards. And it’s a good idea to use tools that allow you to monitor progress across settings.

Research and Resources:

Aleman-Tovar, J., Schraml-Block, K., DiPietro-Wells, R. et al. Exploring the advocacy experiences of military families with children who have disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31, 843–853 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02161-5

DiPietro, R. (October 10, 2025). Personal interview.

Martin, L. T., Trail, T. E., & Jeffries, J. (2025). Assessing the needs of military-connected children and resources to address those needs. Rand Health Quarterly, 12(3), 4. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12218359/#sec3

Military Child Education Coalition. (2022). The benefits and challenges of being a military child. https://militarychild.org/upload/images/MGS%202022/WellbeingToolkit/PDFs/2_EI_Benefits-and-Challenges-of-Being-a-Mil-Child-2022.pdf

Opie, J.E., Hameed, M., Vuong, A., Painter, F., Booth, A. T., Jiang, H., Dowling, R., Boh, J., MacLean, N. & McIntosh, J. E. (2024). Children’s social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes in military families: A rapid review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33, 1949–1967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02856-5

Rogers, M., Johnson, A. & Coffey, Y. (2024). Gathering voices and experiences of Australian military families: Developing family support resources. Journal of Military, Veteran, and Family Health, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.3138/jmvfh-2023-0057

Soto, M., Crouch, E., Odahowski, C., Boswell, E., Brown, M. J., & Watson, P. (2025). Challenges to school success among children in U.S. military families. Military Medicine, 190(7-8), e1621–e1628. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usae506